Chapter 10 Ethical and Legal Issues

10.1 DISCLAIMER

THIS DOCUMENT DOES NOT CONSTITUTE PROFESSIONAL LEGAL ADVICE REGARDING THE AUTOMATED EXTRACTION OF DATA FROM THE WEB (I.E., ‘WEB SCRAPING’). IT IS FOR INFORMATION PURPOSES ONLY AND PRESENTS AN OVERVIEW OVER LEGAL AND ETHICAL ASPECTS THAT MIGHT MATTER IN THE CONTEXT OF WEB SCRAPING PRACTICES.

10.2 Overview

There are no universal and definite guidelines governing when it is ‘OK’ to use web mining techniques for social science research or other purposes. As the Internet continues to evolve and change, so do the legal and ethical guidelines governing Internet research. The goal of this chapter is to provide a (arguably limited) overview of some of the aspects that Internet researchers, lawyers, and legal scholars have identified as relevant. It highlights some key issues concerning the use of automated data collection from the Internet, which have proven to be important factors in legal disputes. As a result of the availability of well-documented legal disputes involving well-known websites, this chapter focuses primarily on the US context (as the most extreme legal disputes in this context have been brought to court there).31

The cases and issues discussed here demonstrate that the legal status of webscraping remains “highly context-specific” Snell and Menaldo (2016). Whether or not it is ‘OK’ to automatically collect data from a specific source is thus dependent on the context of why and how the data is collected, as well as what the collected data is used for. This includes aspects related to the research question at hand (the data source, subjects, extent, and so on), the specifics of the data extraction procedure used (speed, extent, duration, storage, and so on), and, most importantly, whether and how the extracted data is re-published or used for commercial purposes.

Efforts to clarify legal and ethical guidelines are being hampered by the Internet’s rapid evolution. Over 15 years ago, the first guidelines for Internet research involving automated information extraction were issued. Obviously, these guidelines did not include any discussion of what constitutes appropriate behavior when conducting research on Facebook or other social media platforms.32 However, we see an increase in social science research based on automated data collection from social media. And such research has recently encountered legal issues (for example, Giles (2010)) as well as harsh ethical criticism (for example, Kramer, Guillory, and Hancock (2014), Arthur (2014)). Nevertheless, some key aspects of automated web data extraction for research purposes have proven to be relevant and rather constant factors to be considered from a legal and ethical perspective. These can be summarized into three (partly interrelated) dimensions: Resource costs, business interests, and privacy issues.33 The common denominator, and overall origin of ethical and legal issues in the context of applied web mining, is that the provider of the data has a different usage and user in mind when putting the data online than the application a web mining social scientist has in mind when collecting the data. By writing programs that automatically extract and collect data, we break with the paradigm of individual human users clicking their way through the Web via a Web browser.34

10.3 Technical Aspects: Resource Costs

Accessing a webpage is always related to using the server’s resources. Each HTTP-interaction needs bandwidth and server capacity (computational resources). Clearly, one program that automatically collects data from the web is more demanding for a server than one human user visiting the page for the same purpose, leading to higher resource costs. An aggressive web scraper can eat up server bandwidth and capacity in such a way that the user visiting the website via a browser (thus using the website in it’s intended way) perceives the website as slow or, in the worst case, not responsive at all. If a web scraper or crawler is implemented in such a way that it requests data from the same server in parallel, sending hundreds of HTTP requests per second, the scraping activity could be seen as a de facto Denial-of-Service (DoS) Attack, essentially putting the server (at least temporarily) out of business and thereby making the website unreachable for all users. A scraping exercise that is perceived as a DoS attack can likely have serious legal consequences.35

10.3.1 Be polite/“crawler etiquette”

Obviously, between a quasi DoS Attack and a scraper acting as harmless as a human user lies a large gray area. As a rule of thumb, a crawler is considered ‘polite’ if it doesn’t send more than 10 requests per second to the same server (Liu 2011, 313). In general, it is very unlikely that a scraper or crawler is accidentally implemented in such an aggressive way that it would cause the effect of a DoS attack. A programmer would likely have to make an extra effort to speed up the scraping procedure substantially by implementing it in parallel and let it run on many machines simultaneously.

However, crawlers that would never be considered causing a DoS attack might nevertheless be regarded problematic by webmasters and server administrators because they cause too much traffic. Wikipedia, for example, prohibits access to a large number of crawlers that have shown to be too aggressive.36 Note that server administrators and webmasters are usually well aware of the ways crawlers can affect the server’s performance, particularly in the case of large websites that have many visitors. They thus specifically monitor network traffic and server logs to potentially detect crawlers that might be harmful. Simple crawlers are rather easy to detect and will likely be judged based on how fast they visit how many pages and/or whether they repeatedly scrape the same pages.

Server administrators and webmasters might take purely technical measures on their own in order to keep crawlers out. A first step would likely be to disallow a crawler to visit certain pages or the entire website via respective entries in the website’s robots.txt-file. Professional crawlers that constantly and extensively collect data from the web often identify themselves with a unique/specific user-agent name (Google’s crawler that indexes the entire web is called Googlebot) and usually obey to the rules set in robots.txt. It is commonly seen as good practice when crawlers identify themselves with a unique/specific user-agent name, often in combination with publicly accessible information about the crawler (for example, in a website or GitHub-repository dedicated to the crawler; see, e.g., https://support.google.com/webmasters/answer/182072 for information about the Googlebot). This way, a crawler developer can provide explanations about what the crawler does and how the developer can be contacted in case of concerns/questions. Server administrators and webmasters that note the crawler visiting their website can then inform themselves about the crawler in order to assess whether they want to tolerate it. Thus, besides implementing a crawler in such a way that it is not considered too aggressive, obeying the rules in robots.txt as well as being transparent and open about the crawler additionally signals politeness which might likely increase the chances that a crawler is generally tolerated on a website (even in the long run).

10.3.2 Arms and armor races

Politeness, the use of a unique user-agent name, and obedience to robots.txt as discussed above, are essentially aspects of how a crawler/scraper is implemented. While the developer of such a program has thus many options to make the program more or less tolerable for the website’s administrators, these administrators have a number of purely technical measures to (i) assess and identify a crawler and (ii) to prevent it from further visiting the page. In turn, the developer of the crawler can take other measures in order to outsmart the countermeasures of the server side, etc. In a first step, the server administrator might simply disallow the crawler from visiting the page with a Disallow: /-entry in the robots.txt-file. This would be extremely easy to circumvent for the crawler, as it would likely ignore robots.txt anyway by default. Another simple way to circumvent this, would be to change the crawler’s user-agent information to a standard Browser such as ‘Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X x.y; rv:10.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/10.0’ for Mozilla Firefox (running on a MacOS). A natural countermeasure would be to block the crawler’s IP. That is, the server administrator might identify which user is a crawler simply by keeping track of IP-addresses and the traffic they are related to (ignoring user-agent), and then block any traffic from the crawler’s IP-address.37 In anticipation of this, a malicious crawler can try to prevent being blocked by mimicking natural user behavior, for example by taking breaks of random length between crawling iterations and by using different proxy-servers and thus using different IP-addresses. The latter strategy might also be adopted once the malicious crawler’s original IP-address has been blocked. With the current rather easy and relatively cheap access to proxy-servers for scraping tasks, the crawler developer likely has an advantage in the outlined arms and armor race. However, it is crucial to note that, despite the legal gray area, trying to circumvent the server’s countermeasures when it explicitly does not allow/tries to block access, can likely have legal consequences. Thus, when being made aware that the scraping activity is not welcome, it is strongly recommended to openly try to find a solution/an agreement with the website in order to be officially allowed to scrape or to stop scraping otherwise. The general advice is thus: if you get blocked, do not try to get around! Much better: be open, contact the webmaster, try to find a solution together.

10.3.3 Other technical thresholds

Despite the thresholds implemented to prevent a crawler from accessing data after being detected, there might be other technical thresholds in place which might generally matter from an ethical and legal point of view (independently of whether the webmaster takes specific actions against a specific crawler). Most commonly, such thresholds come in the form of log-ins, user registrations, etc. For example, a website might be only open to registered users (Facebook et al.) or might generally try to block non-human visitors by asking visitors to explicitly state that they are not ‘robots’ (see Figure 10.1) and/or posing them questions that are hard to answer for machines (recognize content in images; see Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.1: Google’s captcha (requires only a click in a checkbox).

Figure 10.2: Snapchat account verification (making sure the visitor is not a robot).

Similar to the potential issues arising when actively engaging in an arms and armor race as outlined above, trying to circumvent log ins aimed at keeping crawlers out, might likely be problematic from a legal point of view. In addition to obviously showing an extra effort to build a crawler that can circumvent such measures despite the fact that they are obvious signs indicating the website does not welcome non-human visitors, such log ins are often explicitly bound to the Terms of Service (ToS) or Terms of Use (ToU) of the website. Thus, the use of crawlers in such cases can be seen as an explicit breach of the ToS/ToU.

10.4 Business Interests

Many of the webscraping-related lawsuits brought to court in the US were initiated due to conflicting business interests. Thus, people/organizations have been sued by the owners of a website, not (only) because their scraping activity was technically harmful (causing resource costs) but because the owners of the website understood the scraping activity as more broadly a threat to their business. Often in these cases, the scraping party’s business model would rely on having access to the data (being allowed to scrape it) and the party providing the data would see the scraping party’s actions as harmful to it’s business model. Academics who use webscraping to automatically collect data for a research project usually don’t fall into such categories. However, websites might be extra sensitive to any form of webscraping due to such concerns. When collecting data for academic research purposes it might thus be helpful to keep in mind when and why data providers might react more sensitive due to their business interests. This section gives a brief overview over different legal theories that have proven to be relevant in disputes over automated online data collection when business interests where at stake.38

As most jurisdictions do not have a complete and explicit ‘Internet Law’, the legal borders of automated online data collection are related to different legal theories, many of which have been developed before the Internet emerged. The legal borders can be roughly divided into the categories copyright and contracts (particularly, but not only in the USA)39

10.4.1 Copyright

Suits related to copyright have been brought forward in situations where the scraping party republished/reproduced extracted content. Snell and Menaldo (2016) mention Kelly v. Arriba Soft Corp. as an example of such a case, where the plaintiff sued the defendant for automatically extracting images from it’s website and republishing them in a different format. While reproducing/republishing automatically collected contents in such a way is rather unlikely in the context of a social science research project, it is nevertheless important to be aware of potential copyright infringement when, for example, making the prepared data set publicly available after publishing the final research results. A simple rule of thumb to keep in mind is that legally, copyright infringement depends on how the results of the research project are published.40 For example, are parts of the extracted content presented/republished 1:1 or are only aggregates/summary statistics based on the extracted content published. In the latter case, copyright infringement is very unlikely. Moreover, it is important to consider the explicit and implicit ToS of the website. The ToS usually contain a paragraph concerning copyright.

10.4.2 Contracts

Breach of contract can occur when a website explicitly prohibits crawlers/scrapers to access its contents or generally only allows the non-commercial use of the website. The former can be an issue for academics that rely on web scraping to collect data for a research project. However, websites are probably unlikely to sue on such grounds as long as their business interests are at stake. Snell and Menaldo (2016) mention two illustrative examples:

- Cairo Inc. v. Crossmedia Servs. Inc.: Breach of the website’s ToU which prohibit access to the website with “any robot, spider or other automatic device or process to monitor or copy any portion”. Background: Crossmedia Servs. Inc. provides several websites to distribute promotional information to shoppers, Cairo’s website provides a service for in-store sales information. Cairo was scraping and republishing information content from Crossmedia’s websites.

- Sw. Airlines Co. v. BoardFirst LLC: Violation of Southwest Airline’s ToU, restricting access to Southwest’s website for “personal, non-commercial purposes” by offering a commercial service that helped Southwest’s customers take advantage of the airline’s seating policy and check-in process to obtain priority seating in the front of the plane, thereby arguably harming Southwest’s business interests.

10.5 Privacy

An important legal and ethical border for web mining where business interests might matter much less but concerns regarding academic research might matter much more is privacy. A key question regarding the ethical and legal constraints surrounding the issues of privacy in research based on automatically collected data from the web is whether the research project is officially considered ‘research on human subjects’. This is relevant because universities and research donors usually have binding rules of how such research has to be conducted as well as how it has to be supervised and approved by an ethics committee. Research projects falling under this category have traditionally involved direct interaction of the researcher with human research subjects (such as in psychology or medical research) or obviously sensitive personal data (medical records etc.). The sensitivity of online data might be much less obvious in this regard. A central question researchers have to consider in this context is whether the data is collected directly from persons or not. Related to this is the question of whether the research deals with ‘human subjects’ which in turn is directly connected to the question of how sensitive the research project is perceived regarding privacy issues. Does research based on publicly available personal data on many individuals collected from various online sources also fall into this category? Whether it does at all, and under what circumstances is not necessarily clear, as put by Markham and Buchanan (2012, 4): “Because all digital information at some point involves individual persons, consideration of principles related to research on human subjects may be necessary even if it is not immediately apparent how and where persons are involved in the research data.”

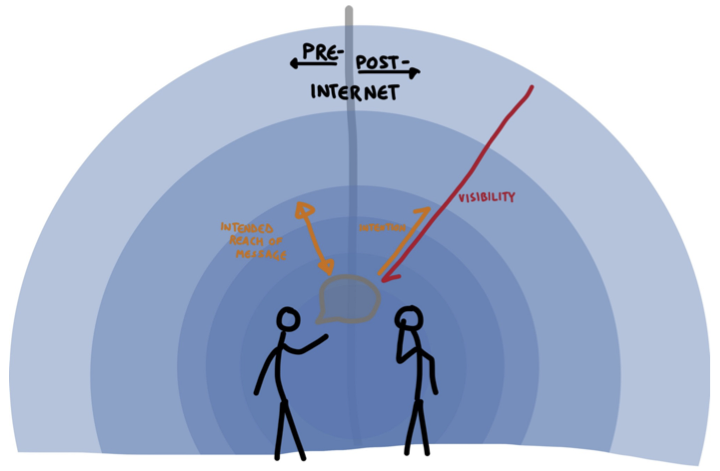

A core issue thereby is what does ‘public’ mean in the age of the Internet. Generally, public information about persons would not be an issue (in the USA) according to O’Brien (2014, 87): “Not all research on humans is subject to the Common Rule [i.e., US rules regarding research on human subjects]. Studies that only use publicly-available information, which potentially includes information mined from the web, have long been an exempt category.” However, O’Brien (2014, 87) also points out that “[u]sers may not fully understand or appreciate the consequences of their actions when they decide to publish, only to later regret them without recourse.” Users might underestimate how hard it is to remove personal information later on as well as the ways in which the published information could be linked with other information about her. What else has this person said online? Who is she connected to? etc. The very nature of web mining makes it relatively easy to collect and link detailed data on human subjects from publicly accessible sources in the web in order to draw a picture that goes well beyond what the person had in mind at each step of publishing bits of this data.

Markham and Buchanan (2012, 5) therefore recommend that one should consider that “[…] privacy is a concept that must include a consideration of expectations and consensus.” What are the ethical expectations users attach to the venue in which they are interacting, particularly around issues of privacy? Both for individual participants as well as the community as a whole?

Figure 10.3: Illustration by Willow Brugh. Source: O’Brien (2014, 88).

10.6 Summary/Questions to Consider

While not providing general definite guidelines, the here explored legal and ethical aspects highlight some of the core issues that should be kept in mind when automatically collecting data from the web for research purposes. Essentially, all legal and ethical concerns depend on to what extent the web mining activity is conflicting with the original usage of the website/data the provider/owner had in mind. For example, using the same web mining techniques to collect data from government websites (that are explicitly aimed at informing the public) or to collect data from a private enterprise whose business model crucially depends on the data provided might well be judged differently from a legal point of view. Conflicts can arise in the technical dimension (does our program obey to “crawler etiquette”?, is it too fast/too aggressive?, does it obey to robots.txt?), the dimension of business interests (does the research project conflict with the business model of the website? is scraped content reproduced/republished? who gets access to the raw data, and for what purposes?), and the dimension of privacy (is the project in the realm of ‘research on human subjects’? to what extent did individuals anticipate this use of their private data when publishing it?).

Being aware of such potential conflicts helps planing a research project accordingly. The more intrusive a crawler program is, the more important it might be to be transparent and open about it and maybe directly find a solution with the website (show good will and clarify that the research is purely academical and non-commercial, as well as clarify how the data will be used). The more likely a research project might fall within the domain of ‘human subjects research’, the more privacy and ethical concerns have to be clarified before starting the project. Being aware of the legal borders helps to further clarify in what way potential conflicts and legal disputes can occur (particularly when a website owner fears that scraping is harmful to its business):

- Copyright: What will be done with the scraped data? will the raw data be published or just aggregates/statistics?

- Contract: Is scraping in line with the terms of use/terms of service of the website?

In almost all cases, legal disputes around web mining are in the realm of civil law (often due to conflicting business interests) and not public prosecution. The latter is usually only triggered when the web mining activity is related to intentionally causing harm (e.g., when it is considered a DoS attack) or when it actively breaches security measures to extract data that is not publicly accessible (hack into online banking systems to extract account information etc.). However, this, of course, depends on the respective jurisdiction (also here, the above stated disclaimer applies!). In the USA, the rules concerning criminal cases are mostly found in the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).

The legal landscape is still evolving while the Internet is constantly changing. Many legal aspects are therefore still unclear, particularly when related to rather novel data sources from the web such as social media platforms. As put by O’Brien (2014, 87), research practices making use of data from such sources “[…] fall into a category of human subjects research in which the legal and ethical standards are unclear.” Independent of the applicable legal framework, researchers using data extracted from the web should always keep a number of ethical questions in mind. Following Markham and Buchanan (2012, 8ff)’s report from the Association of Internet Researchers, important questions include:

- How is the context (venue/participants/data) being accessed?

- Who is involved in the study?

- What is the primary object of study?

- How are data being managed, stored, and represented?

- How are texts/persons/data being studied?

- What are the potential harms or risks associated with this study?

- How are findings presented?

- What are potential benefits associated with this study?

- How are we recognizing the autonomy of others and acknowledging that they are of equal worth to ourselves and should be treated so?

- What particular issues might arise around the issue of minors or vulnerable persons?

Finally, the fundamental ethical principle of minimizing harm should be respected.

References

Another reason to focus on US cases is that a large part of social science research based on automatically extracted data from the Web is concerned with data provided by/hosted by US firms: Facebook, Twitter, Google, etc. Note that the basic logic of when web scraping is very likely not ‘OK’ is likely rather similar in the US and other parts of the world (at least in the realm of developed democracies). Moreover, ethical standards regarding social science research based on automatically extracted data from web sources are likely very similar.↩︎

It should be noted that these guidelines should not be construed as professional legal advice. Rather, they are a set of ethical considerations for Internet researchers designed to make them aware of potential problems.↩︎

Note that these dimensions should not be seen as borders of legal theories with which webscraping might get in contact with. Rather, the categorization into these dimensions aims to clarify along what lines the interests of the web miner and the owner of the website’s content might likely collide and cause conflict.↩︎

Whether or not the distinction between a human user visiting a webpage through a browser or a human user writing a script that visits a webpage is meaningful, is still an open debate. Nevertheless, what is clear is that this distinction is considered as quite relevant by many website owners and it has proven to be relevant from a legal point of view at least in some cases.↩︎

In the US it is under certain circumstances considered a federal crime according to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.↩︎

See comments in Wikipedia’s

robots.txt: https://en.wikipedia.org/robots.txt.↩︎In consequence, any user relying on this IP cannot anymore access any content on that website, neither via a crawler nor via a normal web browser. Note that even if the website’s owner would not try to take any legal actions against the crawler, this can be quite problematic for the user and for other people that rely on the same IP-address.↩︎

Note that while the logic of potential conflicts due to business interests can be applied to situations in many jurisdictions, the actual cases and the specifics of the legal disputes discussed here only refer to the US context.↩︎

More US-specific categories of cases broad to court have involved Violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) or analogous state statutes, trespass to chattels, and hot news misappropriation Snell and Menaldo (2016).↩︎

Generally, attribution does not help. When content is licensed under a creative common attribution (not uncommon for online content), attribution might be sufficient. In any case, when content is reproduced/republished as part of presenting the results of a research project it is crucial to consider potential copyright issues.↩︎