Chapter 2 First steps with R

Before introducing some of the key functions and packages for data analysis with R, we should understand how such programs basically work and how we can write them in R. Once we understand the basics of the R language and how to write simple programs, understanding and applying already implemented programs is much easier. In fact, since R is an open source environment, you can directly look at the source code of R packages in order to learn how they work.

2.1 Variables and Vectors

# a simle integer vector

a <- c(10,22,33,22,40)

# give names to vector elements

names(a) <- c("Andy", "Betty", "Claire", "Daniel", "Eva")

a## Andy Betty Claire Daniel Eva

## 10 22 33 22 40# indexing either via number of vector element (start count with 1)

# or by element name

a[3]## Claire

## 33a["Claire"]## Claire

## 33# Inspect the object you are working with

class(a) # returns the class(es) of the object## [1] "numeric"str(a) # returns the structure of the object ("what is in variable a?")## Named num [1:5] 10 22 33 22 40

## - attr(*, "names")= chr [1:5] "Andy" "Betty" "Claire" "Daniel" ...2.2 Math Operators

R knows all basic math operators and has a variety of functions to handle more advanced mathematical problems. One basic practical application of R in academic life is to use it as a sophisticated (and programmable) calculator.

# basic arithmetic

2+2## [1] 4sum_result <- 2+2

sum_result## [1] 4sum_result -2## [1] 24*5## [1] 2020/5## [1] 4# order of operations

2+2*3## [1] 8(2+2)*3## [1] 12(5+5)/(2+3)## [1] 2# work with variables

a <- 20

b <- 10

a/b## [1] 2# arithmetic with vectors

a <- c(1,4,6)

a * 2## [1] 2 8 12b <- c(10,40,80)

a * b## [1] 10 160 480a + b ## [1] 11 44 86# other common math operators and functions

4^2## [1] 16sqrt(4^2)## [1] 4log(2)## [1] 0.6931exp(10)## [1] 22026log(exp(10))## [1] 10# special numbers

# Euler's number

exp(1)## [1] 2.718# Pi

pi## [1] 3.1422.3 Basic programming concepts in R

2.3.1 Loops

A loop consists a sequence of code that is executed a specific number of times. How often the code ‘inside’ the loop is executed depends on a (hopefully) clearly defined control statement. If we know in advance how often the code inside of the loop has to be executed, we typically write a so-called ‘for-loop.’ If the number of iterations is not clearly known before executing the code, we typically write a so-called ‘while-loop.’ The following subsections illustrate both of these concepts in R.

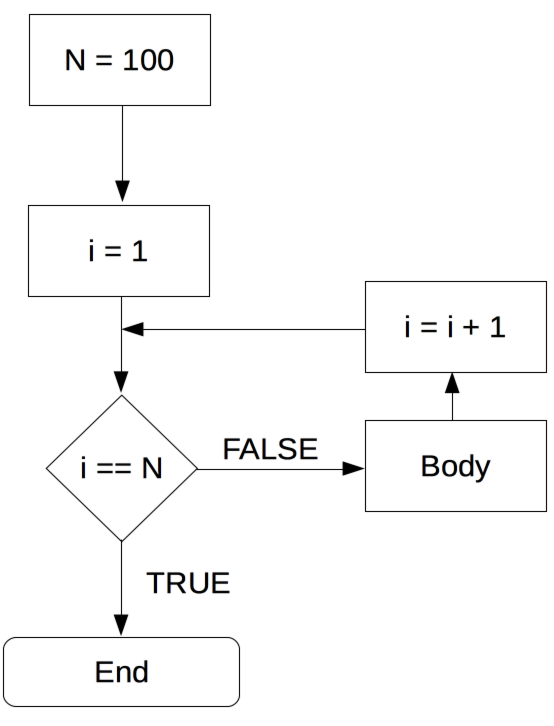

2.3.1.1 For-loops

In simple terms, a for-loop tells the computer to execute a sequence of commands ‘for each case in a set of n cases.’ The following flow-chart illustrates the concept.

Figure 2.1: Foor-loop illustration.

For example, a for-loop could be used to sum up each of the elements in a numeric vector of fix length (thus the number of iterations is clearly defined). In plain English, the for-loop would state something like: “Start with 0 as the current total value, for each element \(i\) of the \(n\) elements in the vector add the element’s value to the current total value.” Note how this logically implies that the loop will ‘stop’ once the value of the last element in the vector is added to the total. Let’s illustrate this in R. Take the numeric vector c(1,2,3,4,5). A for loop to sum up all elements can be implemented as follows:

# vector to be summed up

numbers <- c(1,2.1,3.5,4.8,5)

# initiate total

total_sum <- 0

# number of iterations

n <- length(numbers)

# start loop

for (i in 1:n) {

total_sum <- total_sum + numbers[i]

}

# check result

total_sum## [1] 16.4# compare with result of sum() function

sum(numbers)## [1] 16.42.3.1.2 Nested for-loops

In some situations a simple for-loop might not be sufficient. Within one sequence of commands there might be another sequence of commands that also has to be executed for a number of times each time the first sequence of commands is executed. In such a case we speak of a ‘nested for-loop.’ We can illustrate this easily by extending the example of the numeric vector above to a matrix for which we want to sum up the values in each column. Building on the loop implemented above, we would say ‘for each column j of a given numeric matrix, execute the for-loop defined above.’

# matrix to be summed up

numbers_matrix <- matrix(1:20, ncol = 4)

numbers_matrix## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 1 6 11 16

## [2,] 2 7 12 17

## [3,] 3 8 13 18

## [4,] 4 9 14 19

## [5,] 5 10 15 20# number of iterations for outer loop

m <- ncol(numbers_matrix)

# number of iterations for inner loop

n <- nrow(numbers_matrix)

# start outer loop (loop over columns of matrix)

for (j in 1:m) {

# start inner loop

# initiate total

total_sum <- 0

for (i in 1:n) {

total_sum <- total_sum + numbers_matrix[i, j]

}

print(total_sum)

}## [1] 15

## [1] 40

## [1] 65

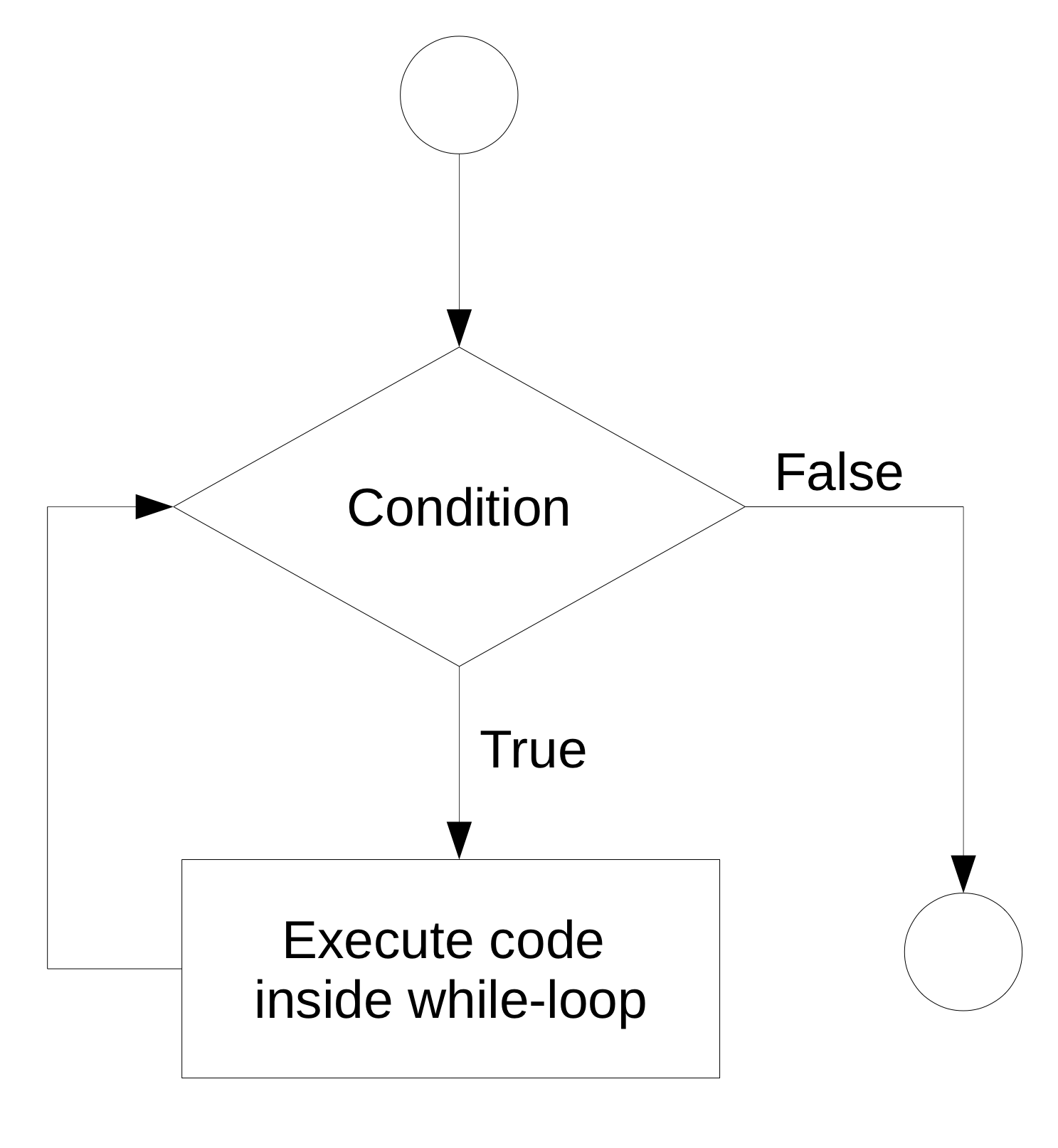

## [1] 902.3.1.3 While-loop

In a situation where a program has to repeatedly run a sequence of commands but we don’t know in advance how many iterations we need in order to reach the intended goal, a while-loop can help. In simple terms, a while loop keeps executing a sequence of commands as long as a certain logical statement is true. The flow chart in Figure 2.2 illustrates this point.

Figure 2.2: While-loop illustration.

For example, a while-loop in plain English could state something like “start with 0 as the total, add 1.12 to the total until the total is larger than 20.” We can implement this in R as follows.

# initiate starting value

total <- 0

# start loop

while (total <= 20) {

total <- total + 1.12

}

# check the result

total## [1] 20.162.3.2 Booleans and Logical Statements

Note that in order to write a meaningful while-loop we have to make use of a logical statement such as “the value stored in the variable totalis smaller or equal to 20” (total <= 20). A logical statement results in a ‘Boolean’ data type. That is, a data type with the only two possible values TRUE or FALSE (1 or 0).

2+2 == 4## [1] TRUE3+3 == 7## [1] FALSELogical statements play an important role in fundamental programming concepts. In particular, they are crucial to make conditional statements (‘if-statements’) that build the control structure of a program, controlling the ‘direction’ the program takes (given certain conditions).

condition <- TRUE

if (condition) {

print("This is true!")

} else {

print("This is false!")

}## [1] "This is true!"condition <- FALSE

if (condition) {

print("This is true!")

} else {

print("This is false!")

}## [1] "This is false!"2.3.3 R Functions

R programs heavily rely on functions. Conceptually, ‘functions’ in R are very similar to what we know as ‘functions’ in math (i.e., \(f:X \rightarrow Y\)). A function can thus, e.g., take a variable \(X\) as input and provide value \(Y\) as output. The actual calculation of \(Y\) based on \(X\) can be something as simple as \(2\times X = Y\). But, it could also be a very complex algorithm or an operation that does not have anything to do with numbers and arithmetic.1 As such, functions facilitate the re-usage of blocks of code that take care of a certain task. Functions take ‘parameter values’ as input, process those values and ‘return’ the result.

When we open RStudio, all basic R functions are already loaded automatically. This means we can directly call them from the R-Console or by executing an R-Script. As R is made for data analysis and statistics, the basic functions loaded with R cover many aspects of tasks related to working with and analyzing data. Besides these basic functions, thousands of additional functions covering all kind of topics related to data analysis can be loaded additionally by installing the respective R-packages (install.packages("PACKAGE-NAME")), and then loading the packages with library(PACKAGE-NAME). In addition, it is straightforward to define our own functions.

2.3.3.1 Compute the mean

For example, suppose we want to compute the mean for several variables. We do so by summing up the elements in a vector with sum() and dividing the returned sum by the number of elements in the vector, which we get with length().

# own implementation: use R-function for summing up the elements in a vector

# and getting the number of elements in a vector

sum(a) / length(a)## [1] 3.667Instead of repeatedly writing the above line of code in a script, we can once define a function called my_mean() and then simply call this function to get the same result.

# define our own function to compute the mean, given a numeric vector

my_mean <- function(x) {

x_bar <- sum(x) / length(x)

return(x_bar)

}

# test it

my_mean(a)## [1] 3.667# compare the result with the function delivered with the R installation

mean(a)## [1] 3.6672.4 Data Structures and Indeces

R provides different object classes to work with data. In simple terms, they differ with regard to how data is structured when stored in in the R environment. This, in turn, defines how we can access specific data values. For example, if we store a bunch of numbers in a numeric vector, we can access each of these numbers individually, by telling R to give us the first, second, \(n\)th element of this vector. If we store data in a two-dimensional object such as a matrix, we can access the data column-wise, row-wise, or cell-wise. Depending on the task, one or the other object class is preferable to store and work with data.

2.4.1 Vectors and Lists

2.4.1.1 Vectors

A vector containing integer (or numeric) values:

# integer

integer_vector <- 10:20

integer_vector[2]## [1] 11integer_vector[2:5]## [1] 11 12 13 14# numeric

numeric_vector <- c(1.4, 5.6, 7.2)

numeric_vector[1]## [1] 1.4numeric_vector[1:2]## [1] 1.4 5.6A string/character vector (‘a vector containing text’):

# character vector

string_vector <- c("a", "b", "c")

string_vector[-3]## [1] "a" "b"2.4.2 Lists

A list can contain objects of differing data types and differing length in its elements, for example a numeric vector and a string_vector:

# initiate a list containing vectors

mylist <- list(numbers = numeric_vector, letters = string_vector)

mylist## $numbers

## [1] 1.4 5.6 7.2

##

## $letters

## [1] "a" "b" "c"We can access the elements of a list in various ways

# with the element's name

mylist$numbers## [1] 1.4 5.6 7.2mylist["numbers"]## $numbers

## [1] 1.4 5.6 7.2# via the index

mylist[1]## $numbers

## [1] 1.4 5.6 7.2With [[]] we can access directly the content of the element

mylist[[1]]## [1] 1.4 5.6 7.2Lists can also be nested (list of lists of lists….)

mynestedlist <- list(a = mylist, b = 1:5)

mynestedlist## $a

## $a$numbers

## [1] 1.4 5.6 7.2

##

## $a$letters

## [1] "a" "b" "c"

##

##

## $b

## [1] 1 2 3 4 52.4.3 Matrices and Data Frames

When working on a data analysis task in R we typically deal with data in a two-dimensional (‘table-like’) format with observations in rows and variables describing these observations in columns. If all variables in a data set are of the same type we can store it in a matrix. In case the variables of a data set are of differing types, we typically store it in a data.frame.

2.4.3.1 Matrices and Arrays

Matrices (or more generally, ‘arrays’) are essentially vectors with an additional dimensionality definition.

# initiate an integer vector

integer_vector <- 1:8

# initiate a matrix based on this vector

mymatrix <- matrix(integer_vector, nrow = 4)The indexing of a matrix is very similar to vectors. However, within the []-expression, we indicate the dimension we want to access with a comma.

# return the second row

mymatrix[2,]## [1] 2 6# return the first two columns

mymatrix[,1:2]## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 5

## [2,] 2 6

## [3,] 3 7

## [4,] 4 8# return the cell in the second row of the first column

mymatrix[2,1]## [1] 22.4.3.2 Data-Frames

Data frames are the most common objects to store/work with data for analytics purposes in R. Most functions to import/load data into the R environment return the data in the form of a data.frame. Technically they are similar to a list with elements of identical length.

# data frames ("lists as columns")

mydf <- data.frame(Name = c("Alice", "Betty", "Claire"), Age = c(20, 30, 45))

mydf## Name Age

## 1 Alice 20

## 2 Betty 30

## 3 Claire 45We can access elements of the data.frame in various ways

# select the age column

mydf$Age## [1] 20 30 45mydf[, "Age"]## [1] 20 30 45mydf[, 2]## [1] 20 30 45# select the second row

mydf[2,]## Name Age

## 2 Betty 302.4.4 Classes and Data Structures

When importing data to R, using a new R-package, or extracting data from web sources, it is imperative to understand how the data is structured in the R-object (variable) one is working with. A lot of errors occur due to giving R functions input in the wrong format/structure. Having a close look at how the data is stored in a variable that we want to work with further can help avoid such errors.2 The function class() returns the class(es) of an R object:

# have a look at the class of the object

class(mydf)## [1] "data.frame"class(mymatrix)## [1] "matrix" "array"To get a clear idea of the structure of data stored in a specific variable, we can call the function str() (for structure) with the object of interest as the only function argument. This is particularly helpful when dealing with a complex/nested data structure.

# have a closer look at the data structure

str(mydf)## 'data.frame': 3 obs. of 2 variables:

## $ Name: chr "Alice" "Betty" "Claire"

## $ Age : num 20 30 452.5 Exercises

2.5.1 Exercise A: Write a Sum Function

In the code example above (introducing the for-loop) you see how we can use for loops to sum up numbers stored in a numeric vector. Use this code example and the following empty function construct to implement a function that takes a numeric vector as input and returns the sum of the vector’s elements.

my_sum <-

function(x){

}Test your function by comparing its output with the output of sum() (the pre-implemented sum function in R) when calling it with the same input.

2.5.2 Exercise B: Robustness and Warnings

Once you have implemented and successfully tested my_sum(), see what happens if you call it with the following vector as input

numbers2 <- c("1", "2", "3")Why do we get an error? Investigate by comparing the vector numbers from the code example above with the new vector numbers2 (the functions str() and class() might help you).

Extend your my_sum() function with a control statement that checks whether the input is of the right class for the function to work (Hint: class(x)!="numeric"). The goal is to make the function more robust to wrong input. That is, if the input is wrong, issue a warning but don’t break down with an error. Use the following code for the warning message:

warning("Wrong input! This function only accepts numeric or integer values!")Test your enhanced sum function with the two input vectors numbers and numbers2.

2.5.3 Exercise C: Standard Deviation Function

In the example above we’ve implemented our own R function to compute the mean, given a numeric vector with the help of already implemented R functions (length() and sum(); alternatively use your own my_sum()). Now implement an R function called my_sd that computes the standard deviation \(SD = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N-1} \sum_{i=1}^N (x_i - \overline{x})^2}\). (Hint: see the math operators section above for some of the ingredients).

Test your implementation by comparing its results with the already implemented sd() function.

2.5.4 Exercise D: Standard Error Function

Building on the function written in Exercise C, implement a function to compute (the estimate of) the sample mean standard error as defined here: \(\text{SE}_{\bar{x}} = \frac{SD}{\sqrt{n}}\). Hint: the idea is to use your own implementation (in Exercise C) to compute \(SD\) as a first step of your standard error function.

Exercises C and D should illustrate how you can approach more complex problems by breaking them up into smaller problems and addressing each of these step-by-step. That is, when looking at the problem of computing \(\text{SE}_{\bar{x}} = \frac{SD}{\sqrt{n}}\), you see that computing \(SD\) is a part of the overall problem, which can be addressed separately.

2.5.5 Exercise E: T-test

Implement a function for the one-sample t-test: \(t = \frac{\bar{x} - \mu_0}{\frac{SE}{\sqrt{n}}}\).

Of course, on the very low level, everything that happens in a microprocessor can in the end be expressed in some formal way using math (and involves binary numbers). However, the point here is that at the level we work with R, a function could simply process different text strings (i.e., stack them together). Thus for us as programmers, R functions do not necessarily have to do anything with arithmetic and numbers but could serve all kind of purposes, including the parsing of HTML code, etc.↩︎

Note that basic R functions as well as functions distributed via R packages are usually very well documented (look up documentation with

help(FUNCTION-NAME)or?FUNCTION-NAME. An important part of such documentations is what class the input arguments of a function must have and what the class of the returned object is. See, for example the documentation ofmean()by typing?meaninto the R-console and hit enter.↩︎